Discovery doesn’t always announce itself with fireworks. Choline chloride drifted into the world of science through slow advances in animal nutrition studies during the early twentieth century. Researchers observed puzzling problems in livestock health and eventually traced these issues to what turned out to be choline deficiency. Cornfields and barnyards showed changes first, long before large-scale production facilities even learned to spell the name. The chemical’s importance got serious attention after World War II, when agriculture boomed and every farm wanted healthy, fast-growing animals. Choline chloride factories grew worldwide, spurred on by the continuous quest to improve feed formulations. The compound migrated out of dusty journals and into feed mills, riding along with the shift toward intensification in agriculture. Today, mentions of choline chloride show up in nutrition textbooks, patent applications, and technical bulletins, anchoring its place as a staple in industrial and research settings.

Choline chloride sells itself as a white, crystalline powder or sometimes as a clear solution. Feed manufacturers add it to premixes, especially for poultry, swine, and fish, because diets without added choline sometimes produce sick animals and disappointing yields. Human nutrition found a use for it too, because people need choline to make acetylcholine, a key brain chemical. As a dietary supplement, it often rides along with B-vitamin blends. The compound also provides an essential input in some industrial polymer and catalyst manufacturing. If you walk through a modern animal feed plant, you won’t miss the big tanks and bags labeled with choline chloride—its regular presence signals the compound’s practical value in production cycles that never really pause.

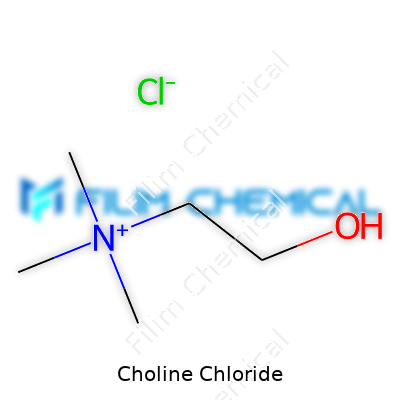

Not every chemical stays easy to handle, but choline chloride holds up well under average warehouse conditions. The pure powder resists clumping as long as it avoids moisture, and the smell carries only the faintest suggestion of fishmeal if left unsealed. Water loves it (high solubility), so no one struggles to blend it in with other feed ingredients. Chemically, choline chloride belongs to the group of quaternary ammonium salts, built around a nitrogen atom linked to four organic groups, one a two-carbon chain handing off to a chloride ion. This structural quirk means the molecule carries a fixed positive charge, which affects how it interacts with living tissues and plants. Labs rely on these predictable properties to synthesize derivatives or modify its functionalities for different applications.

Strict rules keep choline chloride safe for animals and people. Big producers must check for impurities such as trimethylamine, heavy metals, and related byproducts. The powder must reach a defined purity, usually at least 98%. If supplied as a 75% or 70% solution, labels display both percentage and batch data front and center, helping prevent costly mixing errors. Feed-grade choline chloride doesn’t have the luxury of being nearly pure—it needs tight controls because livestock and pets sit at the end of the supply chain. Lesser attention to detail invites major recalls and heavy penalties. Safety data sheets (SDS) ride along with shipments and staff can rattle off hazard codes if pressed during an audit, showing the real-world vigilance that surrounds a chemical with such a broad distribution network.

Large-scale manufacturing of choline chloride starts with two main chemicals: ethylene oxide and trimethylamine. These two react under controlled conditions, often catalyzed by acids, to create choline base, which then absorbs hydrochloric acid to form the chloride salt. The process runs continuously in industrial plants, producing thousands of tons annually. Plant managers stress the need for ventilation and easy handling because trimethylamine stinks and gets toxic at high concentrations. After choline chloride forms, it gets filtered, sometimes crystallized out, and dried or dissolved for shipment. Workers on these lines deal with strong odors and high reactivity—personal protective equipment and leak-monitoring sensors get regular use. Years ago, earlier methods struggled with high byproduct content, but new techniques squeezed out more yield, improved purity, and cut down on waste, showing how continuous process tweaks make scale viable.

Choline chloride doesn’t just work as a stand-alone supplement. Its functional groups encourage creative chemistry in labs and factories. The compound modifies polymers, acting as an ionic liquid precursor or plasticizer. In organic chemistry, choline chloride mixed with urea or other hydrogen-bond donors creates deep eutectic solvents—an emerging class of green solvents that replace more hazardous options for extractions or synthetic reactions. Scientists press choline chloride into new service in plant biotechnology, using it as a methyl donor in crop yield studies or tweaking its structure to generate analogues that help unravel nutrient pathways. None of this would happen without the solid backbone of research that clarified reactivity, showing why industry increasingly depends on this adaptable molecule.

Companies, labs, and regulatory groups don’t always agree on what to call things. Choline chloride answers to a long list of synonyms, including "Choline base chloride", "Vitamin B4 chloride", and "2-hydroxyethyltrimethylammonium chloride." International markets recognize commercial brands as well, with names like "CholiMed," "Vitacholine," and "Cholimax." Some of these brands hint at pharmaceutical grade, while others target bulk feed applications. No matter the label or regional twist on spelling, quality standards tend to follow established nomenclature, helping importers and customs agents identify and track shipments as they cross borders.

Factories and transporters stick to strict safety routines for choline chloride. While not considered highly toxic in small doses, inhalation of powder or vapor during high-speed mixing can burn nasal passages and make eyes water. Operators depend on ventilation, dust control, and respirators in process zones. Bulk storage tanks need regular inspections because moisture triggers lumps and ruins flow. Agricultural suppliers must monitor handling near livestock, since concentrated spills cause digestive upsets in animals. Even storage away from bright sunlight and high heat keeps product losses low. Manuals walk new staff through hazards, disposal routines, and spill management. In my experience with animal feed plant operations, having clean, labeled stations and quick access to PPE made a difference in preventing injury when bulk unloading choline chloride powder.

Animal nutrition holds the biggest share of choline chloride demand. Poultry and swine rations get a regular shot of the compound to prevent fatty liver, muscle weakness, and poor growth—signs that farms learned to spot early. Aquaculture also taps into choline chloride to patch gaps in fishmeal alternatives, supporting healthier feeds as wild fisheries grow scarce. The chemical shows up in pet food, too, where nutritionists mirror findings from livestock studies. In human supplements, tablets and energy drinks use it to support memory or protect liver health, piggybacking on regulatory approvals for food-grade choline. Chemical manufacturers see it as a stabilizer for catalysts, or as a key ingredient in “green” solvents that shrink hazardous waste. My own time consulting for a feed mill highlighted how cost analysis and disease control rely on proven inputs like choline chloride, which makes transitions to alternative nutrients slow and full of risk.

Academic labs and industry R&D centers run parallel races to come up with new uses and more efficient production methods for choline chloride. Some focus on deep eutectic solvent blends, hoping these mixtures reduce the need for petroleum-derived solvents in manufacturing. Veterinary scientists push research into metabolic effects, measuring everything from birth weights in piglets to egg yield in layer hens. Environmental scientists crunch the numbers on runoff and trace residues to understand the compound’s fate in water and soil. Feed companies constantly tinker with microencapsulation and pelletization, seeking to cut waste and improve feed conversion ratios. My experience in research support teams illustrated how multidisciplinary thinking helps stretch budgets and push innovation, whether you're working from grant money or commercial investments.

Tests on choline chloride’s toxicity started decades ago. High doses in lab animals trigger digestive upsets, lower feed intake, and sometimes nerve problems, but these effects hit well above the levels found in commercial feeds. Regulatory agencies set maximum inclusion rates for livestock and human supplements, using decades of feeding trial records. Occasional overdosing in young chicks or piglets does produce fatty liver, growth suppression, or odd behavior, but most production facilities follow dosing protocols tied to feed analysis labs. For humans, most concern starts at doses ten or twenty times higher than recommended, leading to signs like a fishy body odor and hypotension. Environmental toxicology teams study breakdown and bioaccumulation in runoff, but most reports find low risk compared to many agrochemicals on the market. Close records and disciplined batching practices in feed plants guard against accidental excesses, highlighting how careful controls secure animal welfare and food chain safety.

The future of choline chloride looks bright but crowded. As populations grow and protein demand rises, animal feed sectors likely pull in even more product. Trends in plant-based foods and cultured meats generate curiosity about how choline supplementation may support alternative proteins or stabilized vegan recipes. The hunt for sustainable, cost-cutting deep eutectic solvents promises new industrial sales. Biotechnology companies may license novel choline analogues with tailored properties, aiming to influence crop yield, animal metabolism, or pharmaceutical manufacturing. The regulatory environment continues to change, pressing companies to improve traceability and limit impurities. Research into gut health, early development nutrition, and new delivery forms, such as microencapsulated choline, picks up pace, aiming to keep the compound valuable across food, pharma, and industrial circles. Through these shifts, supply chain challenges and price volatility keep buyers and sellers on alert, underscoring the need for continuous innovation and risk management in every corner of the choline chloride marketplace.

Walk through any feed mill or farm supply shop, and chances are you’ll spot bags marked with "choline chloride." Farmers count on it as part of the daily ration for poultry, pigs, and sometimes even dogs or fish. Choline sits at the core of normal growth and development. In my early days on a family-run poultry operation, we learned first-hand how the health of chicks picked up once we added the proper amount of this compound into their feed. It has a direct link to preventing fatty liver syndrome and boosts the growth rate, turning struggling flocks into thriving ones.

Simple things give away its importance. An egg-laying hen with enough choline lays more eggs and produces healthier chicks. Remove it, and you start seeing stunted growth, weak eggshells, and a dip in feed efficiency. It isn’t about getting ahead with expensive supplements, but about supplying a key building block so bodies function as they should.

Choline impacts the brain, liver, and cell health. It helps form acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter linked to memory and muscle movement. Research from the National Institutes of Health shows people need choline for brain development, especially in pregnancy. In animals, choline supports normal nerve signaling, which keeps everything from hatching to feeding running smooth.

It ranks as an essential nutrient for many species since most can’t make enough of it on their own. Feed after feed, nutritionists watch for deficiency symptoms like poor coordination in piglets or missed growth targets in broiler chickens. Feed manufacturers use choline chloride because it mixes well and delivers consistent results—even under stress, heat, or rapid growth demands.

Most choline chloride ends up in animal diets, but some finds its way into vitamins and supplements for people, typically to help cover dietary gaps. With daily meals growing ever more processed and less balanced, deficiencies have become common, especially during pregnancy or for those with certain health conditions.

A few industrial processes also use choline chloride as a catalyst or additive, but those uses lag far behind animal nutrition in volume and attention.

There’s no ignoring the run-off after farms apply feed heavily fortified with nutrients like choline chloride. Excess nutrients, if left unchecked, can enter water systems and cause issues like algal blooms—trouble for both farming and local communities. From experience, farmers and nutritionists constantly work to strike a balance, feeding enough for health without creating waste that damages the land or water.

Precision feeding, soil testing, and research into better delivery systems all play a role. Companies now invest in producing formulations that match the animal’s need with less run-off. Better education and routine nutrient testing help, too—knowing just how much choline is necessary saves money and prevents excessive application.

Choline chloride continues to serve as a workhorse in animal nutrition, supported by decades of hands-on experience and scientific evidence. For many farmers, careful use keeps livestock healthy and productive, and ensures we get safe, high-quality animal products on the table. As with any nutrient, the push for smarter, more sustainable use will shape the next chapter.

People often hear about choline chloride in the context of animal feed or dietary supplements. It’s a nutrient that matters for both humans and animals, playing a role in liver function, brain health, and cell structure. Choline is not just another ingredient on a nutrition label—it forms part of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter essential for memory and muscle control. With growing interest in holistic wellness and performance, the spotlight turns to where choline comes from and how much is considered healthy or even necessary.

Choline chloride serves as one of the main forms of choline delivered in supplements and livestock feed. For years, farmers have added it to chicken, pig, and cattle diets. The goal is not just to improve growth or weight gain but to keep animals from developing liver disease or other health issues—something I’ve seen firsthand on family farms in the Midwest. In humans, choline shapes fetal brain development and prevents certain types of liver damage. The National Institutes of Health recognizes choline as an essential nutrient, rare in deficiency but important enough for prenatal vitamins.

Looking at regulatory guidance, choline chloride passes inspections set by bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority. Both agencies list it as a safe supplement or food additive when used appropriately. For humans, the daily recommended intake ranges from 425 to 550 milligrams, depending on age and sex. Most people get enough by eating eggs, beef, chicken, and certain beans. High doses above 3,500 milligrams per day can trigger side effects—sweating, low blood pressure, or a fishy body odor. Animal studies have shown similar results, though manufacturers adhere closely to nutrition experts’ guidelines to avoid toxicity.

Too much of anything, even a nutrient, can be a problem. Rare cases of choline toxicity in animals have usually involved mistakes in feed formulation, not routine use. Humans sometimes get spooked by the “chloride” in the name, confusing it with industrial chemicals, but what we’re dealing with here is a form naturally found in our bodies and foods. The main thing that raises my eyebrows comes from unregulated supplements sold online. Without batch testing or strict labeling, some products might carry more choline than they claim. That’s risky territory, especially for folks taking other medications or dealing with kidney problems.

Companies that produce choline chloride for human consumption submit their products to purity and safety tests. Labels list the exact amount included. Quality matters—a lesson I learned with vitamins that made me feel odd before switching to a reputable brand. In animal nutrition, feed manufacturers routinely send samples for independent testing. This protects farmers, their animals, and the end consumer who eventually eats products like chicken or beef. The World Health Organization and EFSA agree that following recommended intake levels keeps risk near zero for nearly everyone.

Anyone thinking of adding a choline supplement or feeding choline chloride to animals should talk to a doctor or a licensed veterinarian. Checking labels and trusting only established suppliers helps keep things safe. Regulatory agencies update their recommendations if new research emerges, so staying informed makes sense. For farmers, working with animal nutritionists reduces trouble right at the source. For individuals, eating a varied diet removes most concerns about missing out on this important nutrient.

Folks working on farms know how tricky it gets to keep livestock healthy, especially if feed barely covers all nutritional bases. Choline chloride steps in as an essential part of animal diets, giving poultry, swine, and cattle the tools to grow strong and avoid certain disorders. It acts like a busy helper in the body—making sure fat digests properly and the liver doesn’t get overloaded. In chickens, for example, a little choline chloride in the ration can prevent a drooping, unhealthy look that comes with “perosis,” a leg disorder many old-timers still remember seeing. Years of feed research show choline cutting down on fatty liver syndrome, slowing nerve damage, and boosting overall productivity in egg-layers and broilers alike.

You don’t just find choline chloride in the chicken barn; plant farmers also count on it. In the field, it works as a growth promoter and antistress compound. While crops sometimes get battered by drought or heavy metal stress, adding choline chloride can support them through tough times. I’ve heard small berry farmers remark on healthier foliage after a foliar spray. Researchers noticed wheat and maize took up more nutrients and lived through hot spells with less trouble, which means bigger, healthier harvests. This jump in resilience pays off, especially with the roller-coaster weather we've seen these past years.

Modern, intensified animal production brings tight nutritional margins. Feeding operations sometimes rely on grains and processed ingredients, which often lack natural choline. Choline chloride has filled this gap reliably for decades. Look through industry guidelines—like those from the National Research Council—and you’ll spot recommended choline amounts for swine, dairy cows, broilers, and even fish. Skipping choline can lead to poor weight gain and higher death loss in young animals, which nobody wants. Keeping up with quality feed additives translates into safer, more sustainable food for everyone who relies on dairy, meat, and eggs.

Farmers watch their bottom line. Choline chloride brings a cost-effective, stable source of this essential nutrient, holding up under storage and mixing conditions. This keeps feeding consistent, especially for large, centralized operations. Feed mills blend it into premixes, while some farmers even buy it in bulk. The straightforward science behind its effectiveness—helping build cell walls, shuttling fat around the body, promoting brain and nerve function—encourages trust and adoption across regions. Choline delivers results from large poultry complexes all the way to backyard flocks.

Stewarding soil, water, and input resources is on everyone’s mind. Choline chloride supports efficiency, cutting down on waste by letting animals make the most of their feed. In plant agriculture, its leaf sprays sometimes mean fewer harsh chemicals to combat climate stress. Of course, any additive’s long-term impact should be monitored. Regulatory agencies and food companies want proof that any supplement delivers value without affecting food safety or the environment. Farmers and nutritionists stay on the lookout for new findings, but the long track record of choline chloride gives it a solid standing as a tool for feeding a growing population.

I’ve seen neighbors and large-scale producers alike weigh these options—choline chloride stands out for reliability and real-world impact. Future advances in nutrition might tailor how much and when to deliver choline, matching the specific needs of different animals and plants at each life stage. As pressures mount to grow more food with fewer resources, honest, science-backed inputs like choline chloride will likely stay in the spotlight for farms that feed the world.

The role of nutrition in raising healthy farm animals doesn’t get the spotlight it deserves. Choline chloride, though not as famous as protein or calcium, plays a crucial part in animal diets. It helps form cell membranes, supports liver function, and boosts metabolism. Growing up around livestock, I saw how good nutrition reflects directly in their health and productivity. Choline is one of those small things that make a big difference.

Poultry producers have long relied on added choline, especially for broiler chickens and laying hens. Broilers thrive with 500 to 1,500 mg of choline chloride per kilogram of feed, depending on their age and growth stage. Laying hens need about 250 to 1,200 mg per kilogram, which matches their demand for egg production and growth.

For swine, particularly piglets and sows, nutrition experts point to 500 to 1,000 mg per kilogram of feed. Newborn piglets benefit from levels at the upper end, since their digestive and nervous systems develop quickly. Lactating sows pass choline along to their offspring, so their feed often contains higher choline chloride concentrations. From my experience feeding farrowing sows, meeting choline needs cuts down on litter problems and helps piglets get off to a strong start.

Dairy cattle get their share of attention, too. The cow’s complex digestion, with its rumen microbes, changes how nutrition folks approach supplementation. Even so, adding protected choline to rations has shown real benefits. For lactating cows, rations often have around 40 to 60 grams of rumen-protected choline per day. It helps with liver health during early lactation, especially during metabolic stress when cows struggle to mobilize fat. Cows that get enough choline usually bounce back faster after calving and keep up their milk yield better over time.

Choline isn’t a “miracle ingredient,” but animals suffering from a deficiency show the difference fast. Chickens short on choline grow poorly and develop leg issues. Pigs may deal with fatty liver and poor weight gain. Cattle that don’t get enough risk reduced milk output and reproductive problems. Supplements fill the gap left by feed ingredients with low choline, like corn and some vegetable meals.

Nutrition science changes over time, and recommendations reflect years of trial and error. Not every animal needs the maximum listed dose; health, stage of production, and the type of base feed shape requirements. Feed testing and careful planning help avoid oversupplementation, which can carry its own risks and wastes resources. Veterinarians and feed specialists use feed analysis to spot where choline needs a boost, not just guessing from a chart.

Not every producer has the tools to analyze feed or adjust diets. Small farms and backyard producers sometimes skip choline entirely. They run a real risk: losing out on growth or productivity, and spending more in the long run on vet bills. Using premixes or commercial feeds already balanced for choline helps solve this problem for most operations.

Producers should also pay attention to possible interactions in the diet. High levels of methionine, for example, affect how much choline the animal really needs. Education and access to good nutrition advice help farms stay profitable and animals healthy. It isn’t just about numbers; it’s about giving animals what they need to grow, stay healthy, and produce at their best.

Choline chloride shows up in more places than most people realize. Anyone who’s worked around animal nutrition or compound feed has brushed up against this essential nutrient, which plays a critical role in metabolism and growth. The value of choline chloride only really shines through when it’s stored and handled correctly. Small oversights can mean huge consequences for health, safety, and quality. Over the years, I’ve learned a few tough lessons on the job—lessons worth sharing.

This compound draws water out of the air like a sponge. Left in humid or open spaces, it cakes up fast and loses potency. The smartest move: Store it in sealed containers. Polyethylene drums with airtight lids keep moisture out and cuts down on clumping. Cartons lined with polyethylene bags bring a similar edge for operations working with powder or granular forms.

Temperature swings can create their own headaches. Storage rooms set around 20 degrees Celsius or cooler keep choline chloride from breaking down. Hot, stuffy corners encourage its slow decline. Products lose their edge long before expiration dates roll around if they’re left out in the sun or stuffed by ovens, so a climate-controlled pantry proves its worth over time.

Anyone who’s handled choline chloride by hand knows it doesn’t belong loose in the air. It can irritate skin, eyes, and lungs if dust clouds spread. Simple steps make a big difference: Work with gloves that resist chemical exposure, splash-proof goggles, and dust masks for every batch handled. In tight indoor spaces, local exhaust ventilation removes stray particles from people’s breathing zones.

I’ve seen more than one team underestimate the mess. Spills might look harmless, but sweeping up dry powder clouds the whole area in dust. A vacuum equipped with HEPA filters clears the stuff up much more cleanly than a regular broom. Damp cloths help shine up surfaces without kicking up particles. It comes down to respecting the raw material instead of rushing the cleanup.

The path from warehouse to feed mill to farm rewards care and patience. Simple routines help: Check seals on drums before opening. Make sure dry hands handle packaging. Rotate stock so old product goes out first. Never store choline chloride with acids or oxidizing agents—those don’t mix well, and mixing them can create dangerous reactions.

Old habits often hang on. I once worked with a supplier who stacked new sacks over ancient ones, thinking location didn’t matter. That mistake led to moisture creeping in and ruined half the supply. Since then, I advocate for keeping the oldest stock on top and rotating like groceries in a refrigerator.

Workers new to handling feed ingredients sometimes shrug off safety training, not realizing the long-term risks. A culture built around safety means not just posting rules but talking through why they matter. It means checking up on team members and encouraging questions even on the busiest days.

Choline chloride deserves respect. By storing it in dry, cool areas, checking up on air quality, using the right safety gear, and keeping incompatible chemicals far apart, everyone involved keeps the supply chain running safely. In feed mills, warehouses, or farms, these simple choices pay off in both product quality and peace of mind.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-hydroxy-N,N,N-trimethylethan-1-aminium chloride |

| Other names |

Choline chloride Choline base chloride Choline salt Vitamin B4 chloride |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkoʊliːn ˈklɔːraɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 67-48-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3587263 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:18154 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201472 |

| ChemSpider | 727 |

| DrugBank | DB00122 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.460 |

| EC Number | 200-655-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 1279001 |

| KEGG | C00714 |

| MeSH | D002813 |

| PubChem CID | 6209 |

| RTECS number | KH2975000 |

| UNII | 7V140P89GL |

| UN number | UN9188 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C5H14ClNO |

| Molar mass | 139.62 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Odor | slight amine odor |

| Density | 1.18 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -3.77 |

| Vapor pressure | < 0.01 hPa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 13.9 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 4.2 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -49.5·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.445 |

| Dipole moment | 1.48 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 200.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -430.2 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2700.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA10 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS05 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 160°C |

| Explosive limits | Non-explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3500 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral, rat: 3900 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | FH0700000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 3000 mg/kg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Unknown |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Betaine Choline bitartrate Acetylcholine Phosphatidylcholine Choline hydroxide Choline alfoscerate |